This story is jointly published by nonprofits Amplify Utah and The Salt Lake Tribune to elevate diverse perspectives in local media through student journalism.

While the barracks of the Topaz internment camp in Delta have long since vanished, scholars say the legal framework that imprisoned more than 125,000 Japanese Americans during World War II remains relevant.

This year, eight decades after the camp was dismantled, the Trump administration has pushed to renew the 1798 Alien Enemies Act— a wartime law last used in part to justify Japanese American incarceration. This time, Trump, speaking as a candidate at an Oct. 11, 2024, rally, said he wanted to invoke it as part of his deportation strategy.

“[I intend] to target and dismantle every migrant criminal network operating on American soil,” he said.

In the four months since Trump’s second inauguration, over 250 Venezuelan migrants, identified by authorities as having gang ties with the organization Tren de Aragua, have been deported, according to Secretary of State Marco Rubio. The administration has invoked the statute to detain migrants without court hearings or asylum screenings.

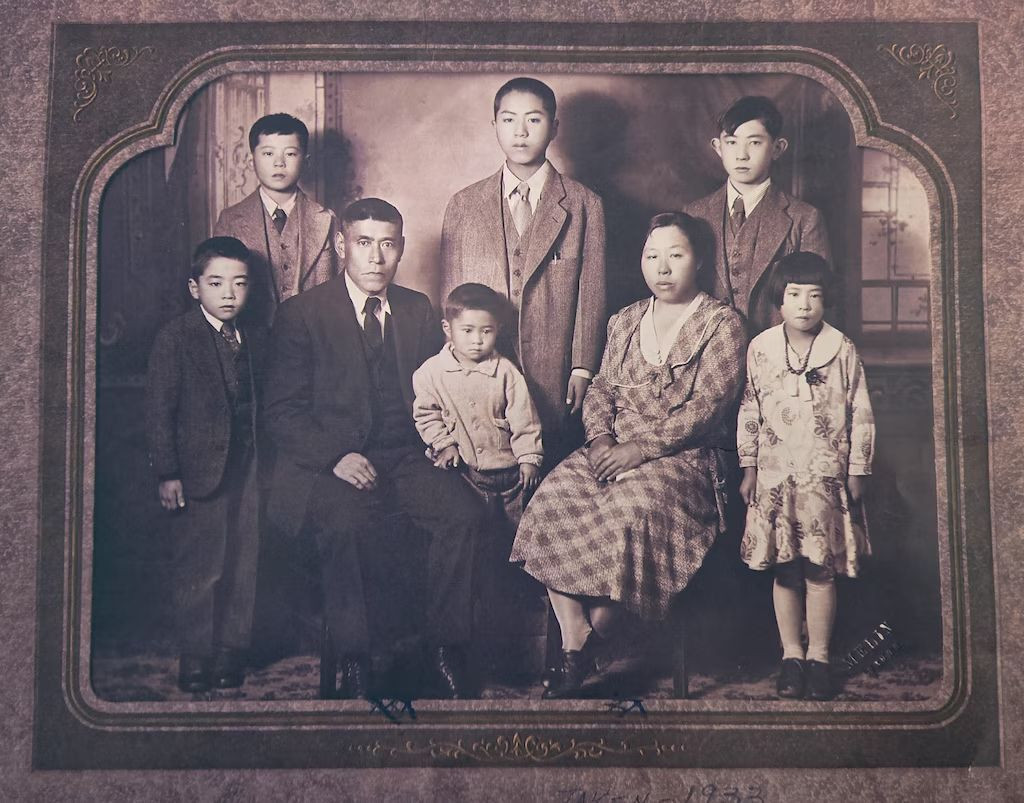

“They're using that law that allowed all the Japanese Americans to be incarcerated,” said Karie Minaga-Miya, whose own mother and uncle were incarcerated at Topaz. “They're using that very same law right now to deport people.”

Matt Basso, a University of Utah history and gender studies associate professor, said this act, historically, has only been issued during times of declared war. The Trump administration has argued the use of the act is justified by what is being defined as an “invasion”— the same term used in the statute’s language.

“The law has slightly larger parameters in the language, but the U.S. legal system is in significant part built on precedent,” Basso said. “Many people have seen this law as rooted in the World War II context.”

On March 15, U.S. District Judge James Boasberg issued an order for the Trump administration to stop deporting Venezuelan migrants. This order, the judge said, was ignored, and the Justice Department argued that the planes carrying the migrants had already left the U.S. airspace.

Now, Human Rights Watch reports the Venezuelan deportees are facing inhumane conditions at the Center for Terrorism Confinement in Tacoluca, El Salvador. The organization, which has investigated human rights abuses for more than 40 years, reports the mistreatment of prisoners includes prolonged isolation, the denial of due process and inadequate access to healthcare and food.

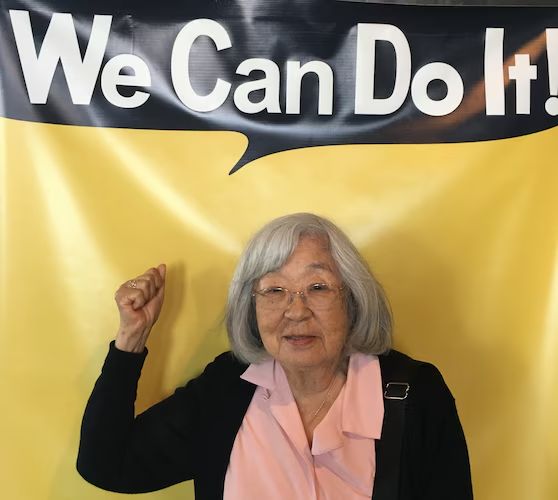

(courtesy Jeanette Misaka) Jeanette Misaka, 94, stands before a "You Can Do It!" banner. Misaka was incarcerated at Heart Mountain in Wyoming, along with thousands of other Americans of Japanese heritage during World War II.

Warnings from the Past

Those with personal connections to Japanese American incarceration warn that, when overlooked, the framing of these events may obscure reality.

For Jeanette Misaka, who was incarcerated at Heart Mountain in Wyoming as a child, these recent deportation actions echo a darker chapter in U.S. history.

“In the beginning, they used the terms ‘relocation, assembly center,’” she said. “That was a euphemism for what really was an American concentration camp.”

The U.S. government’s use of the term “voluntary evacuation” at the time contributed to a distorted public understanding of Japanese American incarceration, said Darin Mano, Salt Lake City councilmember and fourth-generation Japanese American.

“‘Voluntary’ implies that it’s something that you choose to do, and it really was more coercive than it was voluntary,” he said. “Evacuation is a term we use more often for getting somebody out of an unsafe situation, [but] it was based on fear and racism.”

Understanding this history remains urgent, said Glen Feighery, associate professor of communication at the U. and the author of two research articles about the internment at Topaz.

“With historical knowledge, we are in historical times in terms of what is happening politically,” he said.

Alongside Craig Wirth, a veteran documentarian and adjunct associate professor, Feighery led journalism and communication students this spring semester in creating a documentary on the legacy of Topaz.

“History is important, and, quite literally, if we don’t know it, we suffer,” Feighery said.

For Crystal Fraughton, a junior in Feighery’s “Documenting Topaz” class, the goal of the final project is more than remembering past events but understanding the patterns that shaped them, she said.

“It’s not just about knowing the date and that something happened,” Fraughton added. “It is important to understand the signs of it and how it happens and what leads to it if we’re ever going to learn from our mistakes.”

Fraughton noted that her own education had largely overlooked the history of Topaz.

“I knew there had been a camp in Utah, but I was never taught in depth about it in school,” said Fraughton, who grew up in American Fork.

Minaga-Miya said even families with a direct connection to Topaz were often unaware of the camp’s existence and history. She didn’t know until she attended law school, for example, that her mother had been interned at Topaz.

“My mother never talked about it,” Minaga-Miya said. “I just think it’s part of my generation’s responsibility to speak up for our parents or grandparents who were unable to or didn’t want to.”

Misaka said she sees sharing these stories as a way to challenge the silence that has surrounded Japanese American incarceration for generations.

“It's part of our United States history, and it's [not] mentioned very often in the schools,” she said. “But I think that it should be … so that it's not repeated again.”

‘A moral failure’

Despite a lack of public understanding surrounding this chapter of American history, Basso said Japanese American incarceration is now widely acknowledged as a moral failure.

“Almost all Americans understand, I think, what a grave mistake, in hindsight, Japanese and Japanese American incarceration was,” he said.

But, for advocates like Floyd Mori, former executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League, with acknowledgment must come action.

“It’s critical that we speak out very loudly and to bring other discriminated-against people together to make awareness that this is an act of racism and discrimination,” Mori said. “It was bad when it happened then, and it is bad today to have it reoccur.” That understanding, Basso said, requires telling the full story.

“Our history as a nation is complicated, and it is important to know because it can serve as a guide for all folks, all Americans, and others as we consider actions today,” he said. “But we have to know the fullest version and not oversimplify.”

The Day of Remembrance, recognized every Feb. 19, honors those imprisoned at Topaz and other camps and raises awareness of how civil liberties can be compromised in times of crisis, according to the Citizens League. This year, the organization is urging action, noting on its website that the history of what happened to Japanese Americans during WWII, “is not unique.”

“The important element is: don't let it happen again,” Mori said. “You're not going to avoid bad things in history unless you understand history.”

Marissa Bond wrote this story as a journalism student at the University of Utah. It is published as part of a collaborative including nonprofits Amplify Utah and The Salt Lake Tribune.