From inside The Chimichurri Grill food truck parked outside the University of Utah’s Marriott Library, Mariana Galvan shouts, “64!”

Galvan places a white plastic foam takeout container on the ledge of the window and points to a cooler full of sauces and toppings. Her husband, Juan Galvan, works on the next order — a Chimi-Philly sandwich, a choice of steak or chicken, covered with peppers, caramelized onions, cheese and a garlicky chimichurri sauce.

The Galvans’ truck draws hundreds of students each week with a menu that blends diner classics, like the cheesesteak, with South American flavors and ingredients, from chimichurri to queso fresco. The Chimichurri Grill, which first rolled onto campus in 2020, is one of six food trucks at this campus spot, serving food from all over the world.

While the university’s dining halls offer standard options to students, the U. has partnered with truck owners — four of which are family owned — who offer cuisines from Argentina, Iraq, Japan and Afro-Caribbean cultures.

Mariana Galvan said that for owners like her family, the contract with the U. provides stability with a designated spot, consistent foot traffic and catering opportunities at campus events. For students, the trucks offer flavors they can’t get in the dining halls, along with a daily cultural exchange with the truck owners and cooks.

“Most of these food trucks that we have out there are just mom-and-pop operations,” said Jerry Basford, associate vice president for student affairs at the U.

(Evelyn Harris | Amplify Utah) Bento, which serves Japanese cuisine, and Olive's Oasis, selling Mediterranean food, are two of the food trucks stationed in front of the Marriott Library on the University of Utah campus.

Starting the day early

The Galvans, born in Argentina and Mexico, respectively, have lived most of their lives in Utah after their families immigrated to the United States. Their truck’s menu combines North American staples with family cuisines they grew up with, and focuses on chimichurri, a tangy, fresh sauce that is common in Argentinian dishes, Mariana Galvan said.

The Chimichurri Grill’s journey has been an endeavor of love for the Galvans, who have invested 5 years of their lives and created a community at the U., making it a comfortable spot for students who speak Spanish to talk to the Galvans while they grab lunch.

“Our days start at 7 a.m., when we prep everything for the day,” Mariana Galvan said. Mariana, who graduated from the U. with a bachelor’s degree in Spanish teaching, replaced her old 9-to-5 job with the food truck after she wasn’t able to dedicate enough time to running the truck with her family. Now, the truck is the Galvans’ passion, spreading a multicultural taste to students on campus.

“I mean, sometimes I go to the Union, but sometimes you just want something different, you know?” said Ethan Palisoc, a student who is studying Japanese at the U. and grabs a bite to eat whenever he has some extra cash.

(Evelyn Harris | Amplify Utah) Students line up in front of the sky-blue Chimichurri Grill truck at Marriott Plaza on the University of Utah campus.

Compared to the options at the campus cafeteria, like Panda Express, the food trucks offer types of food that students would normally not have access to, Palisoc said.

“It’s like nothing you have ever tasted before, trust me,” said Ghazal Azama, co-owner of Olive’s Oasis.

For Azama, who left Iraq with his family in 2006 for Dubai, moved to the United States in 2011, and has worked in the food industry as a chef ever since, Olive’s Oasis is his family’s way to share their history with every student who places an order, he said.

“Compared to America, the Middle East has a lot more variety in food,” said Azama. “Here, Americans really like their meat and potatoes, but we have a lot more choices back in the Middle East.”

Olive’s Oasis specializes in Mediterranean cuisine, using traditional sauces such as tahini. One of their signature ingredients is falafel, a deep-fried ball made of chickpea or fava beans and packed with spices to bring out a deep, savory flavor profile.

Azama and his family bring another cultural region of the world to the U., giving students a taste of the Middle East on campus, and talking with them to expand both the students’ and their own worldviews.

“You take the experience of your life, put it into the food, and then change it for your customers,” said Azama.

The owners of Bento, Katsu Yamazaki and his wife, Tokiko, have been serving up Japanese comfort food on Marriott Plaza for more than a decade — longer than any other truck operating on campus.

“When I started, food trucks were sort of a trendy thing,” Yamazaki said.

Bento, a Japanese word for lunch box, caught on with both a catchy name and an authentic vibe. Students and faculty stop by every day to try their bowls filled with rice, fresh vegetables coated in a mild sauce and protein ranging from savory teriyaki chicken to breaded tempura shrimp. The truck also offers a regular rotation of specials, including warm curry buns with a doughy exterior.

Yamazaki said he has found loyal customers, and the warm meals and welcoming attitude they have bring year after year of new students to their truck.

“I asked them if I could order in Japanese, and they were like, ‘Yeah, sure!’” Palisoc said.

Over the past decade, Bento has become a staple on campus that students and faculty rely on for lunches year-round, Basford said. “Rain, snow, sleet, hail, it doesn’t matter. Bento is always here,” he added.

‘Eclectic’ options for students

(Evelyn Harris | Amplify Utah) The Chimi-Philly is one of the fan favorite dishes at The Chimichurri Grill, a spin on the classic Philly cheesesteak, stuffed with peppers, steak, caramelized onions and cheese, topped with the truck's signature chimichurri sauce.\

For the last 10 years, Basford has managed the relationship between food trucks and the U., and has worked to expand what he sees as a great opportunity for students. From the beginning, he said, the U. wanted to liven Marriott Plaza, one of the places on campus with the most foot traffic, by providing an “eclectic” palette to students.

The relationship with the U. gives the truck owners stability and routine, Azama said. Outside campus, Utah’s food truck scene operates with much less structure, with trucks relying on groups like the Food Truck League to book events and schedule spots at which to set up. A contract with the U. provides a designated location every day, and clear rules — such as the expectation for a diverse menu, location and food safety — that all trucks on campus must follow.

Trucks on campus also offer options to students with dietary restrictions. Olive’s Oasis provides halal options, while The Chimichurri Grill and Bento offer vegetarian dishes.

The U. reinforces the relationship between the students and these owners by pushing event planners on campus to use contracted trucks, said Basford. Recently, these food trucks have been available at events such as the Soap Box Derby and homecoming, and are a selling point for prospective students.

“When I toured this campus back in high school, part of the pitch from the school was that they had so many food trucks,” said Rebecca Heidt, a student who is studying linguistics at the U.

The trucks serve students who pass through Marriott Plaza daily, but they do more than just serve food. Between classes, students and faculty stop to talk to these entrepreneurs and cooks about their experiences and backgrounds — conversations that don’t often happen when grabbing a salad at the Union.

“Some of the stories you hear from the people who run the food trucks, … it’s amazing where they’ve come from and where they are today,” Basford said.

This exchange goes both ways, Galvan said. While truck owners introduce students to cuisines from around the world, they also meet customers from all over the world.

“We’ve met people from China, Uzbekistan, Bosnia, Spain, Bolivia,” she added. “The best part is that we love what we do, and it shows.”

(Evelyn Harris | Amplify Utah) The menu for The Chimichurri Grill is filled with diner classics like the cheesesteak and dishes inspired by co-owner Mariana Galvan’s Argentinian background, like the "Lomito Argentino.”

Austin Mino wrote this story as a journalism student at the University of Utah. It is published as part of a collaborative including nonprofits Amplify Utah and The Salt Lake Tribune.

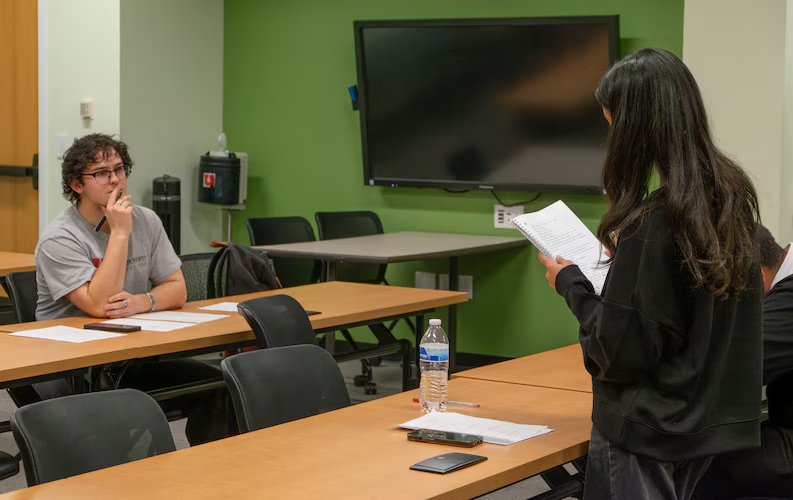

(Leo LeBohec | Amplify Utah) Jeremy Curry-Young, a panel judge, listens to a student present an argument about how lower-income populations may be affected by a carbon tax, at a debate organized by the Refugee Community Debate League at the University of Utah on Dec. 4, 2025. A panel judge, Jeremy Curry-Young, listens to a student speech about how the lower class could be impacted by a carbon emissions tax. (Leo LeBohec)

(Leo LeBohec | Amplify Utah) Jeremy Curry-Young, a panel judge, listens to a student present an argument about how lower-income populations may be affected by a carbon tax, at a debate organized by the Refugee Community Debate League at the University of Utah on Dec. 4, 2025. A panel judge, Jeremy Curry-Young, listens to a student speech about how the lower class could be impacted by a carbon emissions tax. (Leo LeBohec)