Now that he’s 21, Finn Reilly said he’s thrilled to use his ID.

Reilly doesn’t drink, so the allure of tequila shots and cheap beer doesn’t do much for him. But music and entertainment does, and, for his birthday, he wanted to get into Why Kiki to finally join his friends for a night of fun.

“We were able to get a table at the front for their nightly drag show, and it was so special,” he said. “I felt like the belle of the ball.”

Reilly, who loves live shows, said young music fans like him often feel shut out from experiencing Utah arts and culture because of the state’s liquor laws.

“A lot of smaller artists I wanted to see only play in bars,” he said, “and when friends would go up to the 21-plus areas, I didn’t have anyone else to hang out with.”

Reilly said he never had a fake ID when he was under 21 — he hit that milestone birthday on April 3 — but he knows many underage music fans will use them to see their favorite bands.

Kylie Fitch — who’s the marketing director of The State Room Presents, the booking agency that operates The State Room and The Commonwealth Room —said that although “21+” is prominently displayed on the company’s website, ticket stubs, social media and buildings, people still miss the disclaimer and are turned away.

“When we pull in talent that has a younger fan base, sometimes people will miss that and buy a ticket anyways,” Fitch said. “They get angry at us, and we’re like, ‘There’s just nothing we can do.’ We’re doing our best in the state of Utah.”

Whether a venue is all-ages or 21-and-over can divide Utah’s music community along age lines rather than musical taste. Greta Sommerfeld, who is in her 30s, said she appreciates age-restricted venues whenever she goes out for a night in Salt Lake City.

“It’s not about the alcohol for me,” she said. “[Unrestricted venues] remind me of an all-ages nightclub or school dance.”

(The State Room Presents) A line of music fans outside The State Room at 638 S. State St. in Salt Lake City. It's a popular music venue, but is a 21-or-older venue because it serves liquor.

Young fans are affected in more ways than one

Now that he’s 21, Reilly said he can attend events and venues that were previously inaccessible. He said he appreciates Utah’s strict regulations, which make it easier for him to “feel normal being sober,” while still enjoying the entertainment and social aspect bars provide.

“Having something to do on a weekend can keep a lot of kids ultimately out of trouble,” he said.

Some underage fans say they turn to fake IDs to access shows they’d otherwise miss. A few students, who requested anonymity because they use fake IDs, said they agreed with Reilly that venues should welcome fans of all ages.

“The fact that minors aren’t allowed in some venues just because they serve alcohol is ridiculous,” said one student who uses a fake ID to attend concerts.

Utah’s liquor laws, these students said, shut out an “entire demographic” from the music scene. Though they understand the serious consequences associated with using fake IDs, they said they decided the risk is worthwhile to see their favorite artists perform.

“It goes against what music is,” they said, referring to the exclusive nature of 21-plus venues.

Fitch, who grew up on the East Coast, said she sympathizes with younger fans. “When I was a college student and I was under 21, if I had been shut out of concerts at that age, I would be royally pissed,” she added.

Moriah Glazier books events for S&S Presents, which manages Salt Lake City venues like The Depot, Kilby Court and The Urban Lounge. Kilby Court stands out among those as one that consistently accommodates fans of all ages.

“We try our best to match artists with the venue that will allow the majority of their Utah fanbase to attend,” she said. “Due to the availability of venues at any given time, this isn’t always possible.”

Glazier said she hopes younger fans who miss shows will have opportunities to see their favorite artists when they return to Salt Lake City. Glazier’s boss, S&S Presents owner Lance Saunders, acknowledged it’s a challenge to book acts in Utah and comply with the state’s liquor laws, no matter the effect on young fans.

(Francisco Kjolseth | The Salt Lake Tribune) The door into the main stage area of Kilby Court, one of Salt Lake City's most beloved all-ages music venues.

Could the laws change?

Utah’s Department of Alcoholic Beverage Services started in 1935, two years after the repeal of Prohibition — the constitutional amendment that banned the sale of alcohol across the United States. (The Utah Legislature clinched ratification of the 21st amendment, by being the 36th state to vote to repeal.)

The agency’s purpose, according to its website, is “to make liquor available to those adults who choose to drink responsibly — but not to promote the sale of liquor.”

Being a control state, the agency said, removes the economic incentive “to maximize sales, open more liquor stores or sell to underage persons.” Utah is not unique as a control state; 17 other states and a county in Maryland have similar policies.

The agency carries out the state’s alcohol policy, but doesn’t make it — the Utah Legislature decides that.

Both older and younger generations agree that the 2002 Olympics brought changes to Utah’s liquor laws that made venues more accessible. According to the article, one of these included Bud World, which took the Gallivan Center and “featured concerts” and created a “festive atmosphere” including lots of beer, of course.

Venue staff, like Fitch, said they believe more relaxed regulations would boost Salt Lake’s economy.

“Salt Lake is just getting more and more liberal,” she said. “If the city and the state know what’s best in terms of a positive economic impact, they will continue to reshape the laws around alcohol that will keep them from being so stifling for businesses.”

Sommerfeld said she agrees Utah should modernize its approach.

“Surely, there is a way to get the best of both worlds, like making sure underage people don’t get access to alcohol, but also catering to the 21-plus crowd,” she said.

Reilly said he believes there’s potential for places like Area 51, The Beehive and the Granary District as potential models. These spaces host events for mixed-age crowds, serving alcohol to adults with designated wristbands while welcoming younger patrons.

Other states offer a different model, Fitch said, where venues welcome all ages while maintaining connected bars. Fitch said she finds Utah’s split-room approach problematic, describing the user experience as “not great.”

Saunders emphasized that music, not alcohol, remains central to the experience.

“Obviously, it’s nice to have the option of a drink or a snack while you watch the show, but it doesn’t seem like a deal-breaker for most concert attendees these days,” he said.

For Reilly, however, access to 21-plus events provides community.

“A lot of bars here have live music, drag shows and other bigger music events. And it’s nice to have somewhere to go out and dance,” he said. “It’s a third place I usually feel welcome in.”

And that’s why Saunders said this emphasizes Kilby Court’s importance in a restrictive landscape. It’s a space that welcomes any fan or artist, no matter their age.

“In the past, many touring artists have played in rooms that are generally 21-plus,” he said. “That is why we love Kilby Court so much. It’s not just an all-ages venue, it’s a social network with a heartbeat of its own.”

Laney Hansen wrote this story as a journalism student at the University of Utah. It is published as part of a collaborative including nonprofits Amplify Utah and The Salt Lake Tribune.

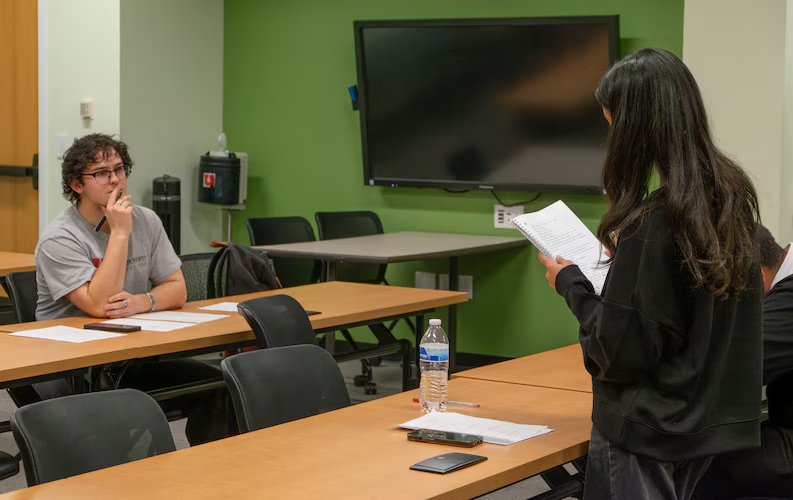

(Leo LeBohec | Amplify Utah) Jeremy Curry-Young, a panel judge, listens to a student present an argument about how lower-income populations may be affected by a carbon tax, at a debate organized by the Refugee Community Debate League at the University of Utah on Dec. 4, 2025. A panel judge, Jeremy Curry-Young, listens to a student speech about how the lower class could be impacted by a carbon emissions tax. (Leo LeBohec)

(Leo LeBohec | Amplify Utah) Jeremy Curry-Young, a panel judge, listens to a student present an argument about how lower-income populations may be affected by a carbon tax, at a debate organized by the Refugee Community Debate League at the University of Utah on Dec. 4, 2025. A panel judge, Jeremy Curry-Young, listens to a student speech about how the lower class could be impacted by a carbon emissions tax. (Leo LeBohec)