After months of work and a delay by the pandemic, Agustin Bautista-Silva presented his mural to a small gathering of students and staff at Salt Lake Community College in April.

“The mural you will see today is a representation of all the times our parents, grandparents, and ancestors wanted us to fly,” Bautista said during the unveiling at the Taylorsville campus. “We all have a similar story.”

Two students pulled back the curtains, revealing a colorful scene depicting a monarch butterfly’s migration from the hands of an individual.

The mural, commissioned by the school’s Latinx Heritage Committee, is emblematic of the journey to the United States that is familiar to many Latinx individuals – either from personal experiences or ancestral stories. The piece, Bautista said, is meant to represent its community on the walls of SLCC.

Agustin Bautista-Silva

In 2005, when Bautista was 10 years old, his mother brought him and his younger brother from their home state of Guerrero, Mexico, to Salt Lake City’s Rose Park neighborhood. College was not in his initial plans.

“I always wanted to join the military,” Bautista said.

He submitted two letters of application while he was still in high school. Despite being a DACA recipient, he said he was rejected because he is not a permanent resident.

“At this point, I didn’t know what I was going to do,” Bautista said. “I had never put any thought into college or studying for a degree.”

Around the same time, during his senior year of high school, an engineering class and a supportive teacher fueled Bautista’s interest in robotics. The teacher encouraged Bautista to apply for college and paid his application fee.

A few months later, Bautista started classes at SLCC.

“I started meeting more people that looked like me and shared my goals,” Bautista said. “I became more attached to the school.”

The connections he made with the Latinx community at SLCC, he said, helped him to stay focused, especially after returning to college following a year-long break, which he took to work fulltime to pay for tuition.

Bautista, who graduated from SLCC in 2018 and received his bachelor’s from Weber State University in electronics and engineering in April, works for the college in the Orientation and Student Success office. When he saw an announcement from the school’s Latinx Heritage Committee seeking submissions for a new campus mural last year, Bautista figured it was a good opportunity to tap into his sketching hobby.

‘I Belong’

As of 2020, Hispanic students account for nearly 20% of the school’s student body, according to the SLCC Fact Book. Sendys Estevez, chair of the Latinx Heritage Committee, said the art piece was proposed to reaffirm the experiences of Latinx students on campus through art.

“We wanted to share our story in the college,” Estevez said.

Orientation and Student Success Director Richard Diaz agreed, noting one of the school’s seven values focuses on inclusivity.

“When you walk into the college, you look for something that makes you say, ‘This is a place where I belong’,” he said. “Our community is very diverse, and so we have to be representative of that diversity not just in our student body but also in our spaces.”

Of the many submissions, Bautista’s topical element of migration represented by the butterfly’s journey resonated with the committee.

“The topic of migration hits a lot of us,” Bautista said. “When you talk to more people, you realize we all share a similar perspective.”

Dreamers

For Brenda Santoyo, who works with undocumented students at SLCC’s Dream Center, the mural offers an invitation of inclusion to Latinx students.

“If someone feels like they belong and feels connected to the campus, they’re more likely to persist,” Santoyo explained.

According to the Utah System for Higher Education, 551 undocumented students attend SLCC as of 2020. This is more than double the next closest institution, Utah Valley University, with 244 undocumented students. These figures reflect students who qualify for in-state tuition.

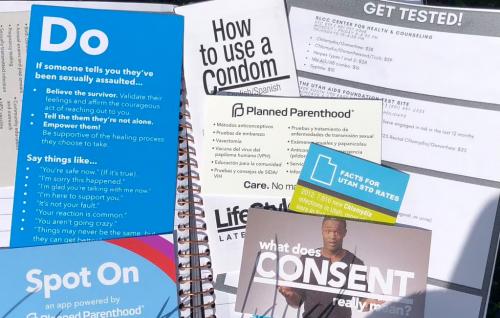

Santoyo emphasized that aside from the mural, initiatives from the Dream Center and the Orientation and Student Success office are available to help Latinx students. For example, the Dream Center hosted its first annual UndocuWeek in April. The week-long event included workshops centered around the lived experiences of undocumented students.

The student success office also offers the Bruin Scholars program, which is designed to aid first-generation, undocumented and non-traditional students by connecting them to resources and dedicated staff.

“If you feel you belong somewhere, it’s more likely you’ll continue and strive for something,” Bautista said.

Legacy

Ultimately, Bautista hopes the mural can help and inspire future Latinx students in similar ways in which he received aid from peers during his time at SLCC.

“Every single person I’ve met along the way, like Richard, the students I’ve interacted with, had a big impact on me,” Bautista said. “You’re doing it not only for yourself but for other people, too.”

For Bautista, the path one creates will be a model for future generations.

“Even though it might not seem like it, every student that graduates is leaving behind a legacy,” he said. “There is always someone out there looking up to you.”